Managing Our Way to Economic Success

williamghunter.net > Articles > Managing Our Way to Economic Success

Two Untapped Resources

by William Hunter, Jan O'Neill and Carol Wallen

Center for Quality and Productivity Improvement, University of Wisconsin, Report No. 4, February 1986. Also published in Quality Progress, July 1987, pp. 19-26.

Practical Significance Two resources, largely untapped in American organizations, are potential information and employee creativity. This report considers them in the context of efforts being made to improve quality and productivity in this country. The use of statistical methods in the U.S. and Japan are compared. It is argued that all employees in an organization should learn statistics. Statistical methods, however, are not a panacea. For example, there must be a transformation of management to ensure, among many other things, that an environment is created in which honest data will be reported and used to improve all processes in the organization.

All employees should always be asking the question. How can we get things to work better around here? Employees must be given tools to handle potential information just as they are given tools for handling goods and services. Both sets of tools are needed to do their jobs if American companies are going to succeed in increasingly competitive international markets. The first steps toward learning and implementing these ideas must be taken by top management. There must be total commitment from the top.

Keywords: Quality, productivity, innovation, management, potential information, statistical methods, design of experiments, process and product design, statistical process control, inspection, quality control, total quality control, employee participation, employee creativity.

In this report I would like to consider some elements of management that are directed to steadily raising the levels of quality, productivity, and innovation in industry. American management will increase their companies' competitiveness in international markets by using some of these ideas. Some of these ideas relate to what is most often called quality control. Speaking in broad terms, it is good to see American companies realizing (1) the in-efficiency of relying on final inspection at the back door to sort out good and bad product and (2) the value of statistical process control. The use of statistical process control reduces the amount of rework and the number of rejects. If it is done well, it can eliminate the need for final inspection all together because all the product that is made is good.

The sad part is that the place where so many American companies are now struggling to get to is the same place that leading Japanese companies have long since left to master even more valuable methods: statistical design of experiments to be used in product and process design, so that, when the manufacturing or other processes are constructed, the products they produce will work reliably. Often times, not only can final inspection be eliminated but also efforts directed statistical process control can be eliminated or at least substantially reduced. I picture a train track going up a mountain with a station called statistical process control somewhere on the side of the mountain. The American train is struggling to reach it in the mid-1980's only to find that the Japanese train departed - uphill - in the early 1960's. We are a quarter of century behind them. Ironically, the two leading figures in helping their train to get started in the 1950's were Americans: W. Edwards Deming and Joseph H. Juran. Japan listened to them. America didn't.

The simple fact is that the way statistical methods are typically used in American companies in quality control and market research bears no resemblance to the thoroughgoing way in which they are used in leading Japanese companies. The use of statistical methods there permeates all functions at all levels of the hierarchy. In many Japanese companies, the president, the line workers, and everyone in between use statistical methods in their work... not just to control quality but to steadily improve quality, productivity, and innovation.

Two Untapped Resources

Potential information emanates from all industrial processes, be they in manufacturing, marketing, administration, or research. A basic decision made by management is whether to use or to waste this potential information. If it is used, potential information can be exploited on a continuous basis to discover better ways to run all aspects of a business ~ to hone operations and adapt them to current market conditions, to improve market research, marketing, research and development, and business plans.

Like potential energy in physics, however, potential information in industry can only be used after it is generated. One reason why some companies have achieved high levels of productivity is that employees have been provided with technical tools for generating, analyzing, and acting on valuable information that they themselves generate. Just as management has given employees excellent tools for producing goods and delivering services, management has also given them excellent tools for working on this potential information. Thus, for example, workers on production lines, in addition to using their brawn to handle product, use their brains to handle information.

Quality, productivity, and innovation can be significantly increased if companies provide all employees with practical tools for exploiting potential information for the benefit of the firm. In summary, there are two enormously valuable untapped resources in many companies: potential information and employee creativity. The two are connected. One of the best ways to generate potential information to turn it into kinetic information that can produce tangible results is to train all employees in some of the simple, effective ways to do this. Rely on their desire to do a good job, to contribute, to be recognized, to be a real part of the organization. They want to be treated like responsible human beings, not like unthinking automatons.

Corporations' Drive Trains

Robert H. Hayes and William J. Abernathy conclude an analysis of American management practices by saying that, "in our preoccupation with braking systems and exterior trim, we may have neglected the drive trains of our corporations." A great deal of power for these drive trains can be generated from the potential information that surrounds all industrial processes. With the right tools, all employees - as detectives - can be involved in this exciting search to discover valuable information that can be used to make the organization more successful.

What tools are needed? As has been demonstrated in many leading corporations (mostly in Japan), statistical methods can be a key element of comprehensive programs to ensure strategic information generation for management action. For the vast majority of the work force these tools will be simple and easy to master. Kaoru Ishikawa, for example, has written a most useful text. It was originally prepared for foremen in Japan to explain seven tools for controlling and improving quality. (QC circles, incidentally, originated in conjunction with educational material prepared for foremen. The material was meant for self-study. Leaders in the quality control movement in Japan recommended that the material be studied by groups of employees - to help one another learn, persevere, and apply new methods on their jobs. These teams were later called QC circles. The reason they were started in Japan was to study, not for the many other reasons that have been cited in Western literature on this subject. As used in Japan, QC circles - because they involve only foremen and first line workers - are only a very small part of what the Japanese refer to as TQC, total quality control.)

The Technical Tool of Statistics

The pivotal nature of the technical tool of statistics has been illustrated by a story about a contest between two individuals. The contest is to see who can be the first to screw some wood screws into soft pine boards. There is a big prize, so both contestants are highly motivated. Only one of the contestants, however, is supplied with a screwdriver. Obviously he wins. The screwdriver represents the technical tool of statistics. The moral of the story is that the U.S., like the contestant without the screwdriver, is at a competitive disadvantage vis-a-vis Japan, and the situation will continue to get worse until U.S. industry makes effective use of statistical tools on a company-wide basis. It is not sufficient to be highly motivated. The meeting at which this story was told by William E. Conway (then President of the Nashua Corporation) to a group of Ford Motor Company managers is recorded on a videotape, which is available from Ford.

The only way to be successful in using statistical methods in a corporation is that the top person must learn simple statistical methods, learn what they can do, get behind the program, and constantly push it in all possible ways. That is, there must be genuine commitment from the top. (Conway has defined commitment in the following manner. Consider a breakfast of ham and eggs. The chicken was involved, but the pig was committed.) Only if top managers decide to get serious about the methods described in this report - to spend the time and effort needed to understand and implement them -- will we be able to use rather than waste the abundant amounts of potential information that exist in our industries to get the drive trains of U.S. corporations in gear and operating at maximum efficiency.

Employee Participation

Active employee involvement - indeed, commitment - is the key to dealing with potential information. This participation, in turn, leads to a widespread process of continual improvement of the systems that make up the company. Management, of course, must not merely provide tools to employees for handling potential information but also must see to it that everyone is

- told about the basic principles underlying the use of these tools so they can recognize situations where different tools should and should not be used (by way of analogy, for example, one should not attempt to pound nails with a saw),

- instructed in the best way to use the tools, and

- encouraged to use them.

Educating employees about these new concepts will result in a vastly expanded reservoir of talent. The uppermost question on employees' minds will be, How can we get things to work better around here? The improvement that results from the use of statistical tools to tackle this question is most often gradual and steady, but it is occasionally abrupt and dramatic. The key is that employees at all levels must have appropriate technical tools so that they can do the following things:

- recognize when a problem has arisen or an opportunity for improvement exists,

- collect relevant data,

- analyze the situation,

- determine whose responsibility it is to take further action,

- solve the problem or refer it to someone more appropriate, and

- ensure that improved procedures are made part of standard operating practice. For example, consider remedies that will eliminate the re-occurrence of a particular problem, or at least reduce the likelihood of its re-occurrence.

As an illustration of one of the central features of this way of running a business, it has been reported that Konosuke Matsushita, the founder of the Matsushita Electric Company,

Statistics Is Not a Panacea

Just using statistical methods throughout an organization is not going to guarantee success. Wise decisions must be made as to which statistical methods should be used by whom. Moreover, experience indicates that more fundamental changes in the overall approach to management must be made first or at least concurrently. See, for example, the writings of Deming, Ishikawa, and Joiner and Scholtes. The central question to ask is whether this approach can achieve results. The success of Japanese industry in making and marketing such products as compact discs, video cassette recorders, integrated circuits, automobiles, motorcycles, steel, cameras, radios, audio tape recorders, watches, and television sets speaks for itself. This approach consists of heavy investment in extensive training of all employees in problem-solving methods such as statistics so that they will be able to participate in important work that must be done by the company and so that information-based management techniques can be used.

Japan's Hardware

Opinions have been expressed that Japan's success in manufacturing the above items can be traced to the use of better equipment, but, as William J. Abernathy, Kim B. Clark, and Alan M. Kantrow have stated, "the evidence suggests that U.S. producers have so far maintained roughly comparable levels of process equipment." This statement has been corroborated by many other observers, including Robert H. Hayes, who reported, "Japanese factories are not the modern structures filled with highly sophisticated equipment that I (and others in the group) expected them to be." What most visitors have failed to notice in Japan is the widespread use of statistical methods: these tools for handling potential information are invisible when compared to the concrete evidence of equipment, the tools for handling physical product.

Statistical methods do not show up in photographs. Robert H. Hayes has observed that

The main thesis of the present report is that the widespread use of the technical tool of statistics has played a central role in accomplishing this slow but steady improvement in so many different operations of Japanese companies.

The Concept of Potential Information

It is useful to imagine industrial manufacturing processes as being a flow of physical product that is changed as it progresses on its way to becoming the final product that is sold. Processes associated with the delivery of services can be viewed in a similar fashion. Potential information emanates from such flows of goods and services. How can this potential information be tapped and used?

Computers and automatic data-loggers have made it possible to collect vast quantities of data. Some people claim that we live in an age of information explosion; others have observed that the situation may be more correctly characterized as one of data inundation. Data are sometimes collected mindlessly, resulting in a veritable flood of numbers overwhelming anyone in its path. Clearly, thought must be given to the questions of what data should be collected. Two mistakes can be made: collecting too little or too much data. What is needed is the strategic generation of information.

Shortly after World War II groups of Japanese came to visit companies in the United States to learn how to make certain products. More recently a group of Japanese visited one of these same corporations, but this time the shoe was on the other foot. The Japanese came as consultants. For a healthy fee they gave their diagnosis. Their main message was that data were not being collected in most locations in the company that they visited and, in those locations where data were being collected, they were not being analyzed effectively. Consequently, said the consultants, the corporation could not possibly understand its processes, and therefore could not control them properly nor improve the efficiency of their performance. Japanese managers, I believe, understand better than their U.S. counterparts the great value that can be mined from potential information.

Everyone Should Learn Statistics

I now outline a simple four-step argument, which has a conclusion of great practical significance. Note that statistics is the science concerned with (a) the efficient generation of data and (b) the effective analysis of data. Assume that your organization wants to increase quality and productivity and that it wants all employees to work toward that goal.

Here is the argument:

- If quality and productivity are to improve from current levels, changes must be made in the way things are presently being done.

- We would like to have good data to serve a rational basis on which to make these changes.

- The twin question must then be addressed: What data should be collected and, once collected, how should they be analyzed?

- Statistics is the science that addresses this twin question.

The conclusion that follows naturally from this argument is that everyone in the organization -- top to bottom, front to back — must learn how to use statistical methods if everyone is to contribute most effectively to the goal of increasing quality and productivity.

In fact, this conclusion extends beyond your own company. It is best for you and your suppliers for their people to learn statistics, too, so they can assure you that their processes are working in a state of statistical control and can guarantee the quality of the goods they are shipping to you. You should also get information from your suppliers on the state of statistical control that existed when the received goods were produced. By working closely with suppliers, you may be able to save money on incoming acceptance sampling procedures because you will be able to rely more heavily on their ability to produce good product and on their data. Furthermore, you can work together to improve quality and productivity and to find innovative solutions to problems, which can be good for both you and them. Depending on the nature of your customers, it may be feasible and mutually beneficial for them to use statistical methods also.

What Can Be Accomplished?

W. Edwards Deming has illustrated one of the troubles with U.S. industry in terms of making toast. He says, "Let's play American industry. I'll burn. You scrape." Use of statistical tools, however, allows you to reduce waste, scrap, rework, and machine downtime. It costs just as much to make defective products as it does to make good products. Eliminate defects and other things that cause inefficiencies, and you reduce costs, increase quality, and raise productivity. Note that quality and productivity are not trade-offs. They increase together.

Within six weeks after Deming introduced some of these ideas to top management in Japan around 1950, there were reported increases in productivity as high as 30% where no new equipment was purchased. It is not unusual to find productivity levels in Japan that are 50% or 100% higher than they are in the United States.

The idea is that senior management concentrate first on improving quality. Find out what your customers want and strive to give them quality products. By contrast, to focus on reducing costs or increasing the volume of production often leads to lower quality and loss of markets.

How Can Success be Achieved?

Innovation, which is important for industrial survival, relies heavily on the creativity and hard work of scientists, engineers, technicians, and others. In research and development work, efficiency can be increased with the wise use of statistical methods for experimental design, data analysis, and model-building. Efficiency in that context is a measure of the amount of useful information obtained per dollar spent. Statistically designed experiments can make a big difference in this context.

After a process is commercialized, further refinements and improvements can be made in discovering better, more effective, and cheaper ways of controlling it so that a greater proportion of the finished product satisfies specifications. The goal is to prevent defective product from being manufactured in the first place, not simply to detect such defective product after it has been manufactured. Moving further upstream, many companies are discovering the economic value of using quality improvement methods in design departments. Currently, there is particular interest in the use of statistically designed experiments in designing robust and reliable processes and products. Some companies are making use of such techniques. Meanwhile statisticians and engineers are doing research to learn better ways of doing this kind of work.

An ambitious undertaking is to search continuously for ways to improve the productivity of the process as it operates, which can be done by making use of information supplied by technical support staff who may continue doing experimental work off-line and reading relevant technical literature. In addition, it is possible to extract information from the operating process itself. How can this be done?

There are two ways to learn from other people, listening to them (as in a lecture) and conversing with them (as in an interview). Similarly, there are two ways to learn from industrial and other processes: (1) passively "listening" to them using such statistical techniques as quality control charts and acceptance sampling procedures and (2) actively "conversing" with then using such statistical techniques as designed experiments and evolutionary operation.

A wide range of statistical techniques is available for application. Simple techniques such as Shewhart control charts, histograms, cause-and-effect diagrams, and Juran (Pareto) diagrams can be used by everyone, including production workers. It is such techniques that hold enormous promise for corporations and other organizations in the United States. More sophisticated techniques may require the use of advanced hand-held calculators, small computers, or even mainframe computers. Naturally, these more complicated techniques would be suitable for use by fewer employees. But the simplest techniques can be understood and applied by everyone. If this approach is to be followed, a massive education effort must be mounted. Judgement and careful planning are needed to ensure that all employees are taught how to use techniques that are the most practical and cost-effective for them.

To ensure the success of a new initiative aimed at getting all employees to contribute actively and effectively as partners in an on-going, continual, never-ending program to improve quality, productivity, and innovation requires both motivation and tools. Although there is an abundance of seminars on productivity that are offered world-wide, they tend to focus only on the motivational aspects; they deal with attitude and psychology. Employees, however, also need to have the technical tools for getting the job done.

We should not simply copy the Japanese and use the same statistical techniques they do, but certainly we should seriously consider the possible benefit that could accrue to U.S. organizations if such tools were widely used. What we have to do is sharpen them up, and modify and extend them for our particular applications, making sure to take full advantage of modern technological developments such as the computer and modern research in such disciplines as statistics. Many applications, however, will not require the use of computers.

What Do the Japanese Say?

A half-page advertisement appeared in the Wall Street Journal on November 12, 1982. It was placed by a Japanese company, Sumitomo Metals. It was headlined, "The most famous name in Japanese quality control is American." That name is W. Edwards Deming. Deming is a statistician after whom the Japanese have named a most prestigious industrial award to recognize companies that have demonstrated an outstanding capability to produce products of consistently high quality. The competition for the Annual Deming Prizes is intense. Winners proudly advertise this achievement in Japan. In fact, the ad in the Wall Street Journal featured a large photograph of the Deming medal. Sumitomo Metals, an early winner of a Deming Prize, ends the ad with these words: "Thanks, Dr. Deming, for helping to start it all."

The Japanese also give much credit for their industrial re-birth after World War II to Joseph M. Juran. Juran has edited a classic book entitled Quality Control Handbook, which contains practical information on (a) the management of quality assurance functions and (b) methods (including statistical techniques) for controlling and improving quality. Deming and Juran have each received the Second Order Medal of the Sacred Treasure, which is awarded by the Emperor of Japan. In this and other ways, the Japanese have recognized these two American experts for helping to put their economy on the fast track.

I took a three-week trip to Japan in November 1985. For two weeks I was part of a group organized by the Philadelphia Area Council for Excellence under the auspices of the Greater Philadelphia Chamber of Commerce. The purpose of the trip was to visit and study the role of management in leading Japanese firms that have adopted the philosophy of TQC, total quality control. Most of the companies had won not only the Deming Prize but also the Japan QC Prize, for which companies can only compete after having won the Deming Prize. The companies I visited were Toyota, Komatsu, Kansai Electric, Takenaka, Aisin Sekei, Canon, and Yokogawa Hewlett-Packard. Among the things I learned were the following:

- Top management is absolutely committed to quality. It is their brightly burning goal as they study, plan, coach, diagnose, facilitate, and generally help their employees reach ever higher levels of customer satisfaction.

- Top management can talk intelligently and in detail about statistical methods, shop-floor operations, long-term and short-term goals of their companies, and other ingredients of TQC.

- Hoshin management is practiced by these companies. TQC is the everyone's concern, and it pervades all aspects of these companies. Activities of American QC departments are in no way comparable to the all-encompassing activities of TQC as practiced in Japan. Robert H. Hayes argues that strategic planning, though much ballyhooed, has been a flop: ends > ways > means. He argues that perhaps the process should go in reverse: means > ways > ends. Hoshin management says both alternatives are wrong. What works best is a two-way flow: Ends >< Means >< Ways

- All employees have been given the opportunity to contribute to the constant, never-ending improvement of all operations. They readily have cone forward with millions of ideas. They are proud of what they have accomplished.

- The Japanese view America's predominant management style (especially as it relates to quality and productivity) as being pathetic, misguided and somewhat comical. (Our hosts were polite and they never said this outright, but that is my reading of their true feelings.)

- Many American companies still think of quality control as being inspection. The largest division of the American Society for Quality Control, for example, is the Inspection Division. Leading Japanese companies were moving beyond inspection and statistical quality control in the early 1960's.

- Even more companies in Japan are now moving to TQC under coaxing from the banks. The banks noticed that the companies that survived the oil shock (as they call it) in relatively better shape were those that used TQC.

- QC circles are operating in tourist shops and night clubs in Japan.

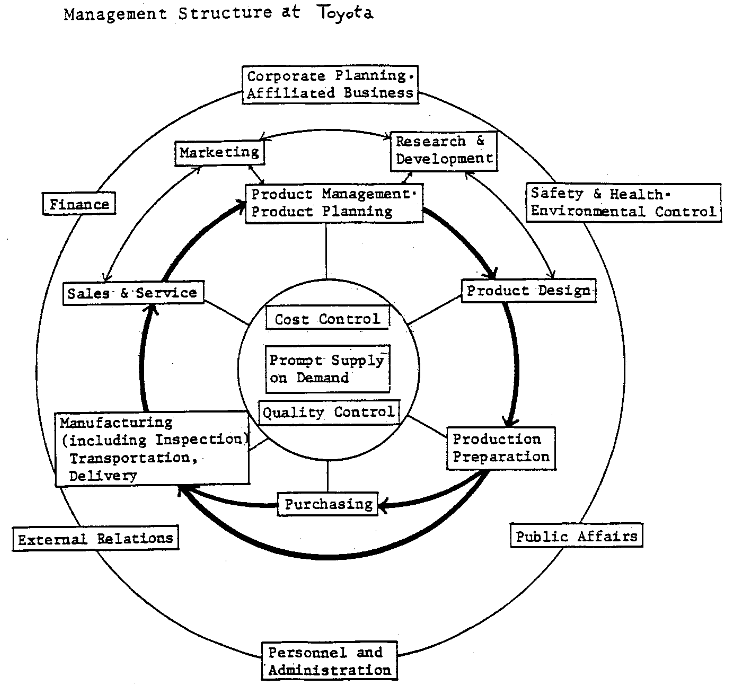

- For companies using TQC, quality is a central goal, whereas finance is considered to be an auxiliary function. See the diagram from Toyota, which is on the following page. (Our business schools reverse the roles of these two things, with quality being so auxiliary that it doesn't even show up in the curriculum.)

- American industries can significantly improve their competitive position if major changes are made in the way they are led. One way to proceed is to adapt to U.S. needs some of the good ideas embodied in TQC and Hoshin management as developed in Japan.

Management Structure at Toyota - Corporate Planning and Affiliated Business

What Do the Americans Say?

Executives in the United States who have studied this philosophy of management, which emphasizes the systematic exploitation of potential information not only to control quality but also to improve it and to increase productivity, recognize that it is a totally new way of managing a business. It entails the use of statistical methods in detecting, thinking about, and solving a wide range of business problems. Donald Petersen , President of the Ford Motor Company, for example, has adopted this approach; he speaks of their new philosophy toward quality and productivity as being a "fundamental change,"

Our goal can be summed up in a few words: to foster never-ending progress.

That goal is central to the Employee Involvement effort, and it is also the underlying impetus of Dr. W. Edwards Deming's management approach, including statistical process control - which we have adopted.

A couple of years ago, I first heard Dr. Deming explain his ideas about American management. His philosophy is summed up best in this statement: "Management has failed in this country. The emphasis is on the quarterly dividend and the quick bucks, while the emphasis in Japan is to plan decades ahead. The next quarterly dividend is not as important as the existence of the company 5, 10 or 20 years from now. One requirement for innovation is faith that there will be a future."

We were impressed with his ideas, and in 1981, we brought Dr. Deming on as a consultant at Ford.

I have been working ever since to become a Deming disciple and to get every member of Ford's management, and those of our supplier companies, to join the bandwagon. Today, every Ford facility is applying statistical management methods. Many of our suppliers are also using this valuable tool. Productivity is not just a conversation piece at Ford - it is an aggressive part of the action.

The Human Dimension

The beginning of the Industrial Revolution ushered in a procession of social critics who have commented - and who continue to comment - on the plight of the worker, and the clash between company goals on the one hand and individual fulfillment on the other. Adam Smith saidp

Karl Marx said,

More recently, in commenting on an article by Donald N. Scobel on labor-management relationships, Russell L. Schroeder, a Field Representative of the AFL-CIO, Region III, has written that the present system in the United States

In his reply to these comments, the author Donald N. Scobel stated that

For handling the physical product "out there" workers are provided tools such as lathes and drill presses. If workers are also provided with appropriate statistical tools for handling the potential information that surrounds all industrial processes and the workers use these tools, then they must necessarily use their brains. Consequently, statistical tools, if they are going to be used, must be internalized. The work to be done is "in here." In brief, by using statistical methods

- to observe,

- to learn,

- to diagnose,

- to think,

- to fix,

- to create,

- to suggest,

each worker becomes more of a whole person and stands a much better chance of achieving individual fulfillment on the job. A situation can be created that will encourage a congruence rather than a clash of individual and company goals. Workers have brains, they have ideas. The opportunity to use statistical methods affirms rather than negates their humanity. Given the opportunity, employees will welcome the chance to function as more complete human beings and to tackle the challenge of always trying to figure out ways to improve the way their processes run, especially if the program is put in terms of working smarter not harder.

Summary

The ideas for the improvement of quality, productivity, and innovation that I have brought together in this article have been influenced by the writings of W. Edwards Deming and Joseph M. Juran , both of whom are consultants and lecturers who have worked in the United States, Japan, and elsewhere. These ideas are also related to those explained by George E. P. Box in his pioneering article on evolutionary operation, a method aimed at increasing the productivity of existing industrial processes. In that article Box expresses the philosophy of evolutionary operation as being to force a process to produce both product and information about how that process can be improved.

Potential information surrounds all industrial processes. Statistical techniques, many of which are simple yet powerful, are tools that employees can use to tap and exploit this potential information so that increasingly higher levels of productivity, quality, and innovation can be attained. Engaging the brains as well as the brawn of employees in this way improves morale and participation...and profits.

Not too many years ago the dramatically increased costs of wasting energy gave rise to successful efforts in industry to conserve energy and use it efficiently. Similarly the Japanese have demonstrated that the costs of wasting potential information can be enormous, and our response should be equally vigorous in meeting this challenge. Serious efforts must be mounted to generate, conserve, and use this potential information efficiently if the competitive position of our industries is to be strengthened. If we are going to see any movement in this direction, senior management must take the lead.

Some readers may say, "Oh, we already use statistics -- in quality control and market research. There's nothing new here for us." But what is being proposed in the present article is not dabbling in statistical methods and using them here or there on a sporadic basis. What is being proposed, on the contrary, is a thoroughgoing overhaul of the way organizations are managed. It is only when everyone in an organization is provided with appropriate statistical tools to tap and exploit potential information that we can ensure that the drive trains of our corporations are working as efficiently and productively as possible. Moreover, statistical methods are only one piece of a bigger picture. What is needed in the United States is a transformation of the American style of management.

In many respects American management has been successful. One of the ingredients of this new approach to management outlined in this report is a focus on quality improvement - for top management making long-range plans and for all other employees working on their jobs day to day. What is called for is constant, never-ending improvement of all processes in the organization. What management needs, too, is constant, never-ending improvement of ideas. What has been presented in this report is some food for thought for managers and others who work in organizations. In the spirit of constant, never-ending improvement of ideas, if you would like to send me comments on this report, I would appreciate hearing from you.

List of footnotes

- Robert H. Hayes and William J. Abernathy, "Managing our way to economic decline," Harvard Business Review. July-August 1980, p.77.

- Kaoru Ishikawa, Guide to Quality Control, Asian Productivity Organization (available from UNIPUB), 1982.

- Richard Tanner Pascale and Anthony G. Athos, The Art of Japanese Management, Warner Books, 1981, p.82.

- W. Edwards Deming, Out of the Crisis, Center for Advanced Engineering Studies, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1986.

- Kaoru Ishikawa, What is Total Quality Control? The Japanese Way, Prentice-Hall, 1985.

- Brian L. Joiner and Peter Scholtes, Total Quality Leadership versus Management by Control, Report No. 6, Center for Quality and Productivity Improvement, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1986.

- William J. Abernathy, Kim B. Clark, and Alan M. Kantrow, "The new industrial competition," Harvard Business Review, September-October 1981, p.74.

- Robert H. Hayes, "Why Japanese factories work," Harvard Business Review, July-August 1981, p.58.

- Robert H. Hayes, "Why Japanese factories work," Harvard Business Review, July-August 1981, p.57.

- Joseph M. Juran (editor), Quality Control Handbook (Third Edition), McGraw-Hill, 1974.

- Robert H. Hayes, "Strategic planning - forward in reverse?" Harvard Business Review, November-December 1985, p. 111.

- Donald E. Petersen, remarks delivered to a meeting of the Society of Automotive Engineers at the Greenbrier, White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia, October 8, 1982.

- Donald N. Scobel, "Business and labor - from adversaries to allies," Harvard Business Review, November-December 1982, p.129.

- Russell L. Schroeder, Letter to the Editor, Harvard Business Review, January-February 1983, p.162.

- Donald N. Scobel, Reply to Letter to the Editor, Harvard Business Review, January-February 1983, p.162.

- Joseph H. Juran, Managerial Breakthrough, McGraw-Hill, 1964.

- George E.P. Box, "Evolutionary operation: a method for increasing industrial productivity," Applied Statistics, volume 6, p. 81.

This research was supported in part by a grant from the Graduate School of the University of Wisconsin-Madison through the University-Industry Research program and a grant from the National Science Foundation (DMS-8420968).

Copyright © 1986 by William Hunter